Introduction

The openness and flexibiliy of current software systems such as Linux have led to rapid advancement and inovation to cyber technology and online services. Meanwhile, this has also created large attack surfaces and security vulnerabilities, which are exploited by email viruses, spyware, trojans, phishing webistes and password snatching malware. Unfortunately, current studies indicate that access control systems of current operating systems are inappropriate and inefficient for non-expert users.

Another problem is, cyber security and cyber attacks are in arms race: once an ideal software security scheme is proposed that can patch all currently existing vulnerabilites, new attack schemes are invented that breaks it. If our target of protection is physical human lives in a smart car, for example, the impact of security breach will be catastrophic, which is already too late to take countermeasures.

To address these problems of complicate access control configuration and innate limitation in software-wise security approach, recent research proposes hardware-based security infrastructure, such as Trusted Platform Module (TPM)[9]. TPM is a secure cryptographic processor, designed to secure CPU and memory by embeddeing cryptographic private keys into devices during the manufacturing stage. These keys never leave the chip, kept secure permanently within the chip. Furthermore, it is infeasible for the attacker even to physically break the chip, because once the chip is open the private key will be permanently deleted, as per its design.

One of the most common use cases of TPM chips is remote attestations[10], which records the execution order of all binaries, kernel modules and dynamic libraries on the memory based on the trust of TPM chip. This execution history recorded by the TPM as a form of a 20-byte or 32-byte cryptographic digest, (so-called SHA1 or SHA256 hash values). Thus, even if the entire system including the OS kernel gets compromised along with the program launch history file managed by the OS kernel in its memory, the system administrator or security analysts still have the opportunity to retrieve the untemperable cryptographic digest securely stored in the TPM chip, which is a 'summary' of all binaries, modules and libraries having been launched since the system's last boot-up.

While the TPM updates the historical summary of all loaded binaries as a single digest value, the kernel also records the hash values of loaded binaries as well as their file name in its own log file. But a powerful malware could compromise the kernel's memory space by using buffer overflow attack, for example, and thereby temper with the kernel's log file, as well as the kernel's task manager. In such a case, a local or remote administrator cannot determine the exact identity of the malware by using the compromised kernel's resource. In such a case, the temper-proof TPM's PCR value can be used to reverse-engineer the identity of the target malware, as its binary value must have been accumulated into the TPM's PCR. However, it's computationally intensive to derive the order of executed programs based on a single crptographic hash value, as there're a large number of possible orderings in launched programs. For example, Linux 4.8 kernel launches about 5000 binaries, modules, dynamic libraries and shell scripts until its boot-up completion. If the system's boot-up sequence has been pre-configured by the system administrator, we know the deterministic order of 5,000 programs to be run, which can be applied during reverse-engineering the given cryptographic digest. But if there was one malware that was possibly injected into somewhere within this order and broke the system's integrity, we have 5,001 possible orderings of the program launch with the malware placed somewhere in the middle, If we have 2 candidate malwares suspected to be injected into the program, there're 12,497,500 possible orderings to be analysed. Since the number of orderings grows exponentially with the number of malware, the computation for cryptanalysis is infeasible for a regular machine. Achieving a high speed in malware detection and analysis is essential in software security, because the faster we can identify malware, more promptly we can take countermeasure against cyber attacks.

In this research project, we use OpenAcc and CUDA to study and demonstrate the feasibility of cryptanalyzing TPM's digests and thereby exactly identify the malware injected into the target machine.

In section 2, we overview the mechanism of TPM's remote attestation and how to leverage OpenAcc and CUDA in this use case. In section 3, we explain the implementation details of the scheme. In section 4, we shows the experimental results. In the final section, we summarize our findings and discuss the future work.

Background on TPM

Trusted Platform Module (TPM) is a temper-proof security chip which communicates with the main CPU chip and works independently from the CPU and memory. Thus, even if the CPU and memory gets compromised, they cannot peep into or temper with the TPM chip. TPM chip is temper-proof not only from cyber attacks but also from physical attacks. The secrecy of the private RSA key stored in TPM is the root of trust, which is never exposed outside the TPM. The architecture of TPM comprises two majore components: software integrity measurement and remote attestation.

Software integrity measurement is a process that the information of the software loaded on the memory is collected and stored as a form of a summarized digest. In particular, when the computer system boots, the TPM uses an non-invertible hash function to compute a fingerprint (i.e. summary) of a loaded binaries (i.e. executables, kernel modules, dynamic libraries) and shell script commands. Each loaded binary is hashed and fed into the hash function again with the next loaded binary. Thus, each computed hash value is a summary of all loaded binaries so far.

These hash values are used for attesting the established code stack to remote provers. A code stack is the software launch history from the initial booting until "now", which includes the system BIOS, bootloader and kernel image. The code stack's signature can be represented as a recursive cryptographic hash of the binary files as input values. Every computational step of the code stack signature gets over-written into the TPM chip's same internal PCR register.

We cannot arbitrarily modify the PCR register's value, because it is physically outside our CPU. Thus, software attacks cannot tamper with TPM and its PCR, due to this hardware protection setting.

So if a malicious software runs before or after the authorized program, its binary will get accumulated into TPM's PCR register, and the final software stack's signature will become a different value than what we expect. This way, we know that some unauthorized program was/is running on our computer.

Remote attestation is a mechanism a client (prover) can authenticate its hardware and software setting to a remote server (challenger). The goal of remote attestation is to allow an challenger to verify the integrity of a remote prover's platform by using an untemperable hardware prover.

Overview

Problem Definition

Suppose we cannot run a task manager because our task manager got compromised by the malicious program. So the only way for us to investigate the identity of the malicious program is by looking at the TPM chip's PCR register value. Given a list of all known malicious program's binaries and our expected software stack signature, we reverse-engineer (i.e. re-compute the recursive SHA1 in a brute-force way for all possibilities) and determine: which malicious program(s) were/are running on our compromised computer?

Parallel Computing

The larger our software stack's size is (i.e. the more programs we have launched), the longer it'll take to brute-force and determine the malicious program's identity. And the larger the number of candidate malicious programs is, the longer it'll take to brute-force and determine the malicious program's identity.

As the software stack size increases linearly, our the search space grows exponentially. As the number of candidate malicious programs linearly, our search space grows linearly. We can use Odyssey to test and determine the feasible maximum size of the software stacks and the feasible number of malicious programs.

To accomplish parallel computing, we first leverage OpenAcc (open acelerators), which is a C++-based parallel programming standard whose gaol is to simplify parallel computing of heterogenius CPU and GPU systems. OpenAcc is a high-level programming component to abstractize data transfer between the CPU and the accelerator. In particular, OpenAcc pragmas are used as compiler directives in order to specify parallel regions in the source code. Then, OpenAcc compiler processes data between the host and accelerators. When OpenAcc is used in C/C++, the length of dynamically allocated arrays must be specified in advance. By doing so, the OpenAcc compiler can pad array dimensions on the accelerators to enhance memory alignment and execution performance. In addition, variables/arrays of struct or class are processed in a special way.

Our architecture also leverages CUDA which is another parallel computing platform and API. CUDA is a software platform that gives direct access to GPU's virtual instructions and parallel computing elements. Although GPUS are widely used in game industries for graphics rendering and game physics calculations, CUDA-enabled GPUs can be utilized for general-purpose processing (GPU). Such examples include non-graphical applications in cryptography, computational biology and scientific calculation.

CUDA platform is accessible through CUDA-accelerated libraries, compiler directives suchas OpenAcc/OpenMP and standard languages such as C/C++/Fortran. In addition, CUDA also supports other computational interfaces including OpenCL, DirectCompute, OpenGL and C++ AMP. Furthermore, third-party wrappers can be used in Python, Perl, Java, Ruby, Matlab, R, Mathematica and IDL.

Terminology

The following defines two key entities used in our TPM-enabled system booting and remote attestation between two machines.

- P: prover computer to be attested by the challenger

- C: challenger computer to attest the prover

- TPM: prover computer's TPM chip

P has its own TPM chip, and C knows this TPM chip's public key. TPM chip's private key is known only to TPM itself and never leaves the TPM chip. It's almost impossible to even physically break the TPM chip to learn about this key.

TPM-enabled System's Booting Procedure

The following steps describe how a TPM-enabled prover machine (P) boots up in tandem with TPM's integrity measurement.

Step 1) Turn on P machine's power

Step 2) P (BIOS) → TPM : computes & sends GRUB2 bootloader binary's SHA1 hash

Step 3) P (BIOS) : loads and launches GRUB2 Bootloader binary on memory.

Step 4) P (GRUB2 bootloader) → TPM : computes & sends Linux kernel binary's SHA1 hash

Step 5) P (GRUB2 bootloader) : loads and launches Linux kernel on memory.

Step 6) P (Linux kernel) → TPM :

a) computes and sends every startup program binary file's SHA1 hash just before launching each. (e.g. firefox, vim, gedit)

b) computes and sends its every dynamic program loader file's SHA1 hash just before launching each. (e.g. ld.so in case of Linux)

c) computes and sends every dynamically shared library file's SHA1 hash (e.g. .so files in case of Linux) just before loading each. (e.g. libc.so, libcrypto.so)

d) computes and sends every Linux kernel module file's SHA1 hashx before mounting each. (e.g. bluetooth, video, wifi modules)

The TPM internally updates its currently stored SHA1 hash by chronologically computing:

In this mechanism, if ever one program element in the above launch process (e.g. Linux kernel) is a defected version, its binary file will have a different value in the defected part and thus its computed SHA1 hash by the GRUB2 bootloader to be extended into the TPM chip will be completely a different value than the expected one. The challenger (C) can remotely check if the value stored in the target computer's (V) TPM chip is our expected value or not, and thereby check if all programs loaded on the system is safe to be used and if the prover computer (P) is currently in a safe state.

The order of launching programs is important, because it represents our root of trust chain. In our design, our root of trust is BIOS (or UEFI). That is, we fundamentally trust that BIOS will correctly compute the GRUB bootloader binary file's SHA1 hash and send it to TPM. Once this holds and if GRUB bootloader is compromised, its computed SHA1 hash by BIOS to be stored in the TPM will be a different value, and thus by checking the currently accumulated SHA1 hash stored in the TPM we can detect any abnormality on the loaded program. Once the compromised GRUB bootloader is loaded, it cannot modify the TPM's current value to our expected value, because SHA1 computational answer space is very large and it is infeasible to find a value B such that SHA1 (A ⊕ B) = our expected value. The same mechanism applies to all possibly defected user programs, dynamic libraries or kernel modules. Before they get launched, the Linux kernel always computes their SHA1 hash and extend it to TPM. Thus, once the compromised component starts running, it cannot cheat on the TPM's stored value to trick us into believing that the computer is in a safe state.

Remote Attestation Protocol

The following describes the remote attestation protocol between the challenger (C) and prover (P) machine. For this part, we implemented the remote attestation code in the verfiier and challenger machine by using IBM's TSS library.

Step 1) C → P : Sends a random challenge number and asks

to send the current SHA1 hash stored in P machine's TPM. The challenge number is to prevent a

replay attack (will be explained)

Step 2) P → TPM : sends P's challenge number and asks to sign (e.g. RSA) and give its currently stored SHA1 hash.

Step 3) TPM → P : signes its currently stored SHA1 hash with the challenge number and sends them back

Step 4) P → C : sends its TPM's signed SHA1 hash, the challenge number, its X509 certificate and the kernel's binary launch log file

Step 5) C : Verifies the X509 certificate and then verifies the TPM's RSA signature on the signed SHA1 hash and challenge number

(to check if this is a true SHA1 hash approved by the TPM). The role of the challenge number

is to guarantee that this signature was created uniquely for this request with this challenge number,

thus a malware cannot illegally reuse this signature in the future, because the future request will

have a different challenge number. Thereafter, it checks if the SHA1 hash is the same as our expected value.

If the certificate and signature are verified but the hash does not match the expected value according to the launch log,

C creates and tests all possible combination of candidate malware(s)' SHA1 hash(s) into P machine's program launch history's

sequence until C gets the same value signed by the TPM. Once we find the matching value and matching

sequence, we can identify what the malware(s) is and exactly when it was launched.

Parallel Computing: OpenMP and CUDA

The core part of our project is to leverage parallel computing for malware identification. We used two different designs: in the first design we used OpenMP. In particular, we used OpenMP pragmas in the forloops inserting the candidate malware into each possible position in the software boot-up sequence. The major challenge is to select all possible combination of malware in the scenario we have more than 1 malware injected. We used recursive function calls to find all malware combinations, and whenever each malware combination is found at the end of recursion the context entered into OpenMP-enabled nested forloops. It is reasonble to perform malware combination search outside the OpenMP region because combination search overhead is considerably smaller than the nested forloops computing millions of SHA1 hashes.

In the second design we used CUDA instead of OpenMP. We removed OpenMP pragmas and converted the nested forloops into a CUDA kernel function. We used cudaMalloc() and cudaMemcpy() functions to copy the array of malware definition and the array of executed binaries. One challenge we faced was that the SHA1 fucntion is originally implemented in the dynamic Linux crypto library, which cannot be executed in the GPU. To address this issue, we compiled our program by using a static version of crypto library, instead.

Evaluation

System Setup

For the first experiment of remote attestation protocol, we used To implement remote attestation, we used a server with LG’s UEFI firmware. The firmware implemented the TPM 2.0 specification[1]. At boot time, the firmware extended a PCR with a TPM-aware version of the GRUB2 bootloader[2]. GRUB2 then extended the PCR with a TPM-aware version of the Linux 4.8 kernel. The kernel used Linux’s Integrity Management Architecture subsystem [4] to automatically extend the PCR upon the loading of kernel modules and user-mode binaries. Internally, the subsystem used a Command/Response Buffer (CRB) device driver[5] to communicate with the TPM; the CRB protocol is the standard device interface for TPMs[6]. The CRB driver exposed the TPM to the rest of the system via /dev/tpm0. Our server-side attestation daemon was a user-mode process which leveraged the IBM TSS library[7] to ask the TPM for quotes.

For the second experiment of malware identity analysis, we used Harvard University's Odyssey[8], which is a large-scale heterogeneous high performance computing cluster which can run computationally intensive scientific simulation and modeling. Each node contains from 8 to 64 core united of Intel and AMD-based x86_64 architectures. Each node uses 12GB to 512GB RAM, where 4GB/core on average. There are also 1,000,000 NVIDIA GPU cores for high-speed parallel computing. Its storage unit size is 35 Petabytes. We emulated different network latencies and bandwidths by using tc-netem[11] and tc-tbf[12].

Remote Attestation Experiment

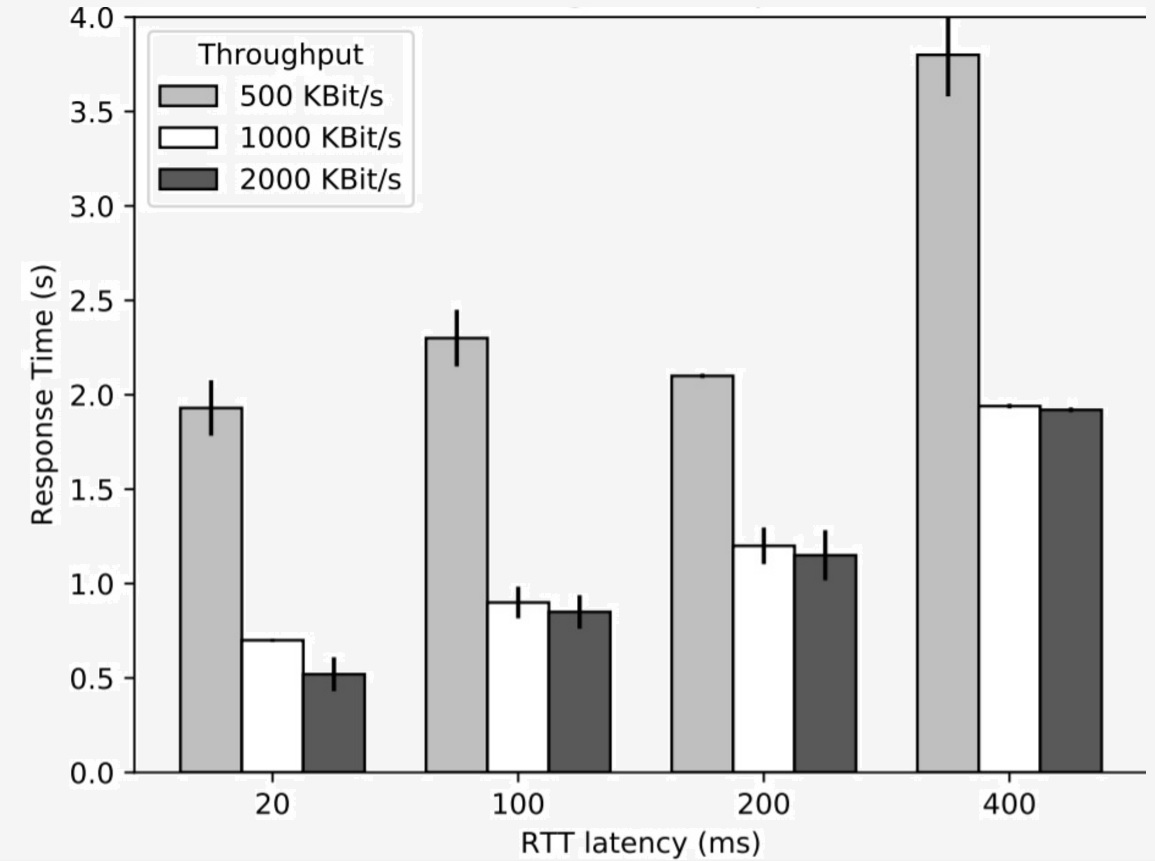

Figure 1 shows the challenger-perceived delays of the remote attestation protocol across different network delays and bandwidths scenarios. The PCR value's quote size was 89 bytes, PCR[10]'s SHA1 hash was 20 bytes, X509 certificate was 150 bytes, and a log of hash values recorded by the prover. This log includes every binary's pathname (e.g., /bin/sh). The pathname can be used as extra information for the challenger to reverse-engineer the loaded components in a more detailed way. Our prover booted at runtime level 3, where the full kernel image and its device drivers were loaded, but no GUI manager. The number of loaded binaries were 200 files, whose gzip compression yielded 26 kilobytes. Figure 4 illustrates the expected patterns. The attestation delay becomes higher with the increasing network latency, but decreases with the increasing bandwidth. Our latency did not get any lower beyond 2Mbps. As typical bandwidths of mobile connections are around 20MBps (10 times higher than our maximum bandwidth), the desicive factor of the remote attestation delay will be the network latency.

One interesting finding was that a single TPM quote signing operation took 225ms, while a TPM PCR read operation took 20ms. We speculate that the larger delay of quote signing was attributed to the computationally expensive RSA signing operation, which would take longer in a small TPM chip than high-end CPUs.

OpenMP and CUDA Experiment

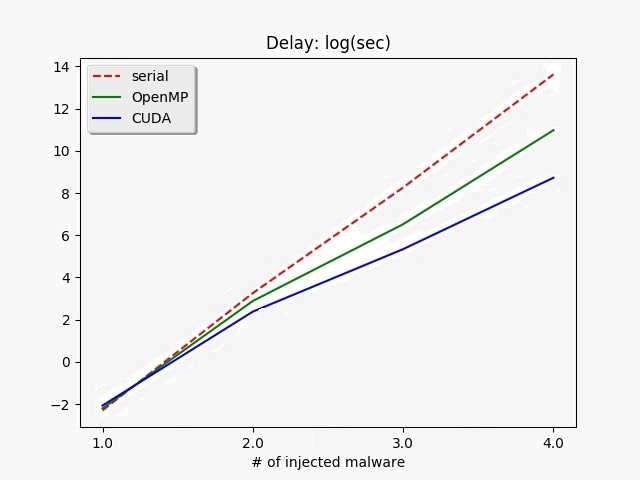

Figure 2 depicts malware detection delays for serial, OpenMP and CUDA computing. In particular, the delay represents the execution time for multiple SHA1 computations. Since we had 200 binaries executed in the boot-up software stack, whenever we injected 1 additional malware in the boot-up sequence, it incurred 200 times higher execution time. Therefore, 1, 2, 3 and 4 malware injections respectively incurred 200, 2002, 2003 an 2004 SHA1 computations.

As Figure 2 illustrates, OpenMP gained upto 10x speedup compared to serial computing, and CUDA gained upto 100x speedup. This is an expected result as Odyssey's GPU (CUDA) has many more cores than CPUs (OpenMP) and thus is faster in vectorized computation.

We could not experiment more than 4 malware injections, because its computational time would be expected to be around 500 hours for CUDA and 5000 hours for OpenACC! However, we figure that simultaneous injection of 4 malware would be a reasonably sufficient practical scenario for a robust system.

Conclusion

In this project we explored how to leverage parallel computing to analyze malware intrusion and reverse-engineer the code stack digest recorded by TPM. Then we demonstrated that it is feasible to determine the exact identity a small number of intruding malware which belongs to our discovered malware list by leveraging parallel computing based on OpenAcc and CUDA.

One limitation of our current malware identification solution is that it cannot detect self-modifying malware[3], because such code can arbitarily modify its binary sequence without impacting its functionality. It is not feasible to define all such random variation of the same malware family in our malware definition list. To this end, our future research is to efficiently detect and determine the identity of randomly modified malware from the same family while leveraging a temper-proof TPM.

Source Code

Our source code can be found in this Github repository. Download "utils.zip" and "ReadMe.docx".

References

[1] Trusted Computing Group. TPM 2.0 Library Specification,

https://trustedcomputinggroup.org/tpmlibrary-specification/

[2] CoreOS. GRand Unified Bootloader 2.0,

https://github.com/coreos/grub

[3] Self-modyfing code,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Self-modifying_code

[4] Linux. Integrity Measurement Architecture,

https://sourceforge.net/p/linux-ima/wiki/Home/

[5] Linux. TPM 2.0 support for FIFO and CRB interfaces,

https://lwn.net/Articles/624241/

[6] Trusted Computing Group. TPM 2.0 Mobile Command Response Buffer Interface,

https://trustedcomputinggroup.org/wp-content/uploads/Mobile-Command-Response-BufferInterface-v2-r12-Specification_FINAL2.pdf

[7] IBM. TPM 2.0 TSS,

https://sourceforge.net/projects/ibmtpm20tss/

[8] Harvard University' Odyssey,

https://www.rc.fas.harvard.edu/resources/odyssey-architecture/

[9] Kinney, Steven. Platform Configuration Registers. In Trusted Platform Module Basics, 2006

http://doi.org/10.1016/B978-075067960-2/50007-5

[10] Coker, G., Guttman, J., Loscocco, P. et al. Int. J. Inf. Secur. Principles of remote attestation. In International Journal of Information Security(2011) 10: 63.

doi:10.1007/s10207-011-0124-7

[11] The Linux Foundation. netem.

https://wiki.linuxfoundation.org/networking/netem

[12] The Linux Foundation. Token Bucket Filter manpage.

https://linux.die.net/man/8/tc-tbf